Author questionnaire #1: James Tabor on the historical Mother Mary

Introducing our new interview feature.

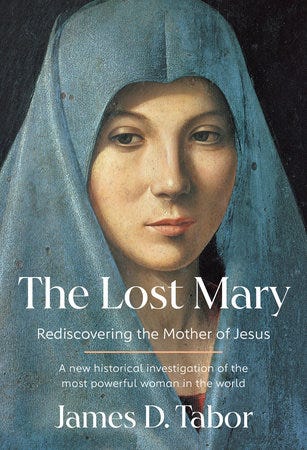

At Idea Architects, we have the honor of working with today’s leading visionaries. In our new interview series, we aim to highlight each of their books as they publish. In our first edition, Dr. James Tabor provides a seasonally appropriate look into his account of the historical Mother Mary in The Lost Mary, available for purchase wherever books are sold.

How do you describe The Lost Mary to the potential readers you meet?

I usually begin by saying that Mary, the mother of Jesus, is the most famous woman in human history—and at the same time one of the least understood. Billions of people know her through art, prayer, and devotion, yet almost no one has ever been invited to meet her as a real historical person. The Lost Mary sets out to recover that woman: a Jewish mother from Galilee, living under Roman occupation, raising a large family in dangerous times, and standing at the heart of the movement that later became Christianity.

Rather than focusing on later theology or devotional tradition, the book asks a simple but radical question: what can we responsibly say about Mary if we place her back into her first-century Jewish world? Drawing on archaeology, ancient texts, and social history, I try to restore her humanity—her motherhood, her courage, her grief, her resilience, and her influence. In doing so, Mary emerges not as a passive figure on the margins, but as a central presence in the lives of Jesus, James, and the earliest Jesus movement. Readers often tell me that once they meet this Mary, they can never quite see the familiar images in the same way again.

How did you first become interested in the subject?

My interest in Mary developed gradually over many years of studying early Christianity, particularly the family of Jesus. As I worked on Jesus, James, and John the Baptizer, I kept running into the same puzzle: Mary was everywhere and nowhere at the same time. She is present at the beginning of the story, and she is there at the end—but in between, she almost disappears.

At the same time, I was spending decades excavating and studying the landscapes where Mary actually lived—Galilee, Sepphoris, Jerusalem, Mount Zion. Standing in those places, reading the texts alongside the archaeology, I became increasingly convinced that Mary’s story had been flattened by later tradition. The more I looked, the more I realized that recovering Mary was not a side project—it was essential to understanding Jesus and the origins of Christianity itself.

What was the most surprising thing you learned while researching and writing?

What surprised me most was how much evidence had been hiding in plain sight. When you read the New Testament closely, in conversation with archaeology and Jewish history, small details begin to connect in unexpected ways. Mary’s repeated marginalization, the emphasis on Jesus’s brothers—especially James—and the early silence about Mary’s later life all begin to make historical sense once you understand the theological pressures that shaped the tradition.

I was also struck by how profoundly dangerous Mary’s world was. She lived through mass crucifixions, political terror, and dynastic violence. Two of her sons were executed. This context transforms familiar texts, like the Magnificat, from pious poetry into something closer to a revolutionary manifesto. Mary was not sheltered from history—she survived it.

What do you hope readers take away from The Lost Mary?

Above all, I hope readers come away with a deeper appreciation for Mary as a fully human being. Recovering the historical Mary does not diminish her significance—it restores it. Her faith, strength, and endurance become more compelling, not less, when we see what she actually endured.

I also hope the book encourages readers to think differently about how history and theology interact. The Lost Mary is not an attack on faith; it is an invitation to see how devotion can sometimes obscure the people it seeks to honor. By bringing Mary back into her Jewish world, we gain not only a richer understanding of her life, but also a clearer picture of Jesus and the movement that followed him.

About the author: James D. Tabor is a historian of ancient Judaism and early Christianity and a retired professor of religious studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he served as department chair for ten years. He previously taught at Notre Dame and William and Mary. He has authored ten previous books, including the international bestseller The Jesus Dynasty. For over three decades, he has combined textual research with archaeological fieldwork and is co-director of the Mount Zion excavation in Jerusalem. His work has been translated into more than twenty languages and featured in major international media.

P.S. Sascha Landry, Doug’s assistant, will be leaving the company in the new year, and we are looking for her replacement. If you or someone you know is interested in being a crucial administrative part of our team and getting an inside look at how the magic is made, please check out the job post.